Obsolete

A photographer wonders if he’ll be replaced by a machine

Generations have grown up with the idea of being replaced by machines, beginning with the first ones who were – the hand weavers who were put out of business by automated looms at the beginning of the industrial revolution. They rose up behind Ned Ludd, a mythical weaver, and smashed mechanized looms and mills in the Midlands until their rebellion was crushed by executions and transportation to penal colonies. It was doomed, in any case, by the simple fact that everyone who wasn’t a hand weaver was happy with the profits and convenience of machine-made cloth.

You won’t find a lot of people today who’d be willing, like the original Luddites, to take up arms against the convenience that technology has brought to our lives. Automation, assembly lines, industrial technology and computers have made goods cheaper and generally better, and though there’s still a lingering unease with how fast and connected our lives have become thanks to computers and digital technologies, it’s something most of us ignore while we enjoy 24/7 communication and entertainment at a nominal cost.

Occasionally, though, some new technological development inspires a surge of unease. In 2022, it was the emergence of a new generation of easy to use Artificial Intelligence with creative applications – software such as ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, Midjourney and Deep Dream Generator. There had been similar AI applications made available to the public before, but the new generation was suddenly producing results that far exceeded their results.

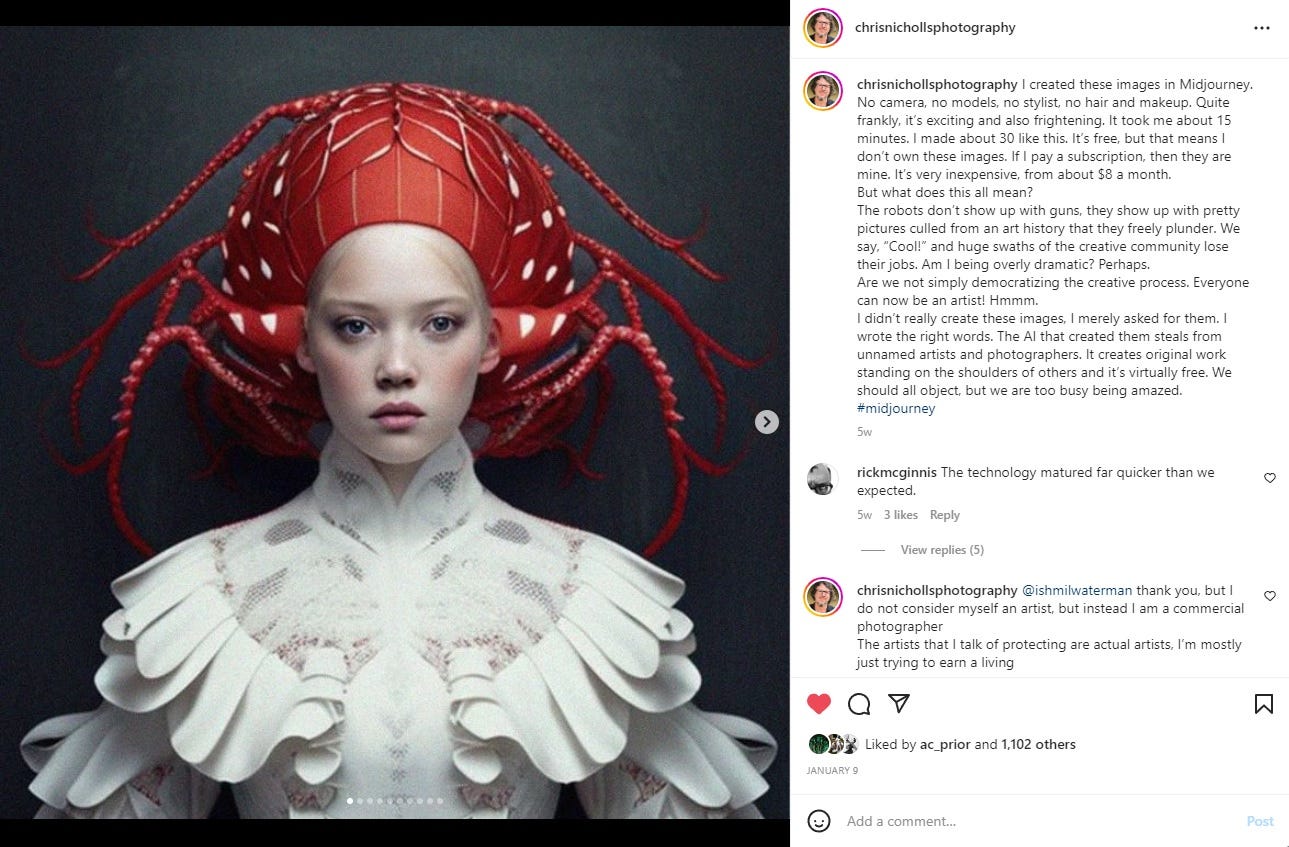

The results were so impressive that people – writers, artists and photographers, many in my circle – began playing around with the software and posting results. On Instagram, accounts began popping up in my feed devoted to AI-generated imagery, but I really noticed when a colleague of mine here in Toronto, photographer Chris Nicholls, posted a set of images on his IG feed, the results of a session in Midjourney.

They stood out from his work, but they were striking nonetheless, though it was what he wrote in the post that struck me. “I didn’t really create these images,” Chris said. “I merely asked for them. I wrote the right words. The AI that created them steals from unnamed artists and photographers. It creates original work standing on the shoulders of others and it’s virtually free. We should all object, but we are too busy being amazed.”

I was amazed, to be honest. There was, to be sure, something undeniably off about these images – some consistent violation of texture and proportion and verisimilitude that only got worse the more I looked at the AI images that were suddenly flooding my social media feeds. But they were miles ahead of previous attempts made by computer software to create realistic pictures of the world or people.

While image creation programs like Midjourney were certainly advancing by leaps and bounds, it was obvious to me that text-generating AI such as ChatGPT had crossed over that sometimes funny, sometimes eerie uncanny valley that had made AI so deficient in the past. In a PM Chris suggested some stories to read, including a New York Times story from last April where author Steven Johnson had written:

If you spend enough time with GPT-3, conjuring new prompts to explore its capabilities and its failings, you end up feeling as if you are interacting with a kind of child prodigy whose brilliance is shadowed by some obvious limitations: capable of astonishing leaps of inference; possessing deep domain expertise in a vast range of fields, but shockingly clueless about many basic facts; prone to strange, senseless digressions; unencumbered by etiquette and social norms.

This was certainly true, but it was clear to me that AI text-generating software was more than capable of taking over low-level writing chores, like authoring press releases, recipes or simple technical manuals. Besides photography, the other string to my late career income-generating bow these days is writing freelance custom content, and I could certainly imagine a day, perhaps not that far in the future, when AI would take that job away from me.

As Chris wrote in a comment on his original IG post:

You know when robots started replacing factory workers I thought that the creative community was immune to its advances, but now I have been proved wrong

It certainly may expand creativity into new and exciting areas and I don’t want to sound like an old man shaking my stick at progress, but I do worry that many creative people will lose their jobs as corporations will always be looking for cheaper and faster

Still, the train has left the station and probably the smart thing would be to get on that train, because you can’t stop progress.

I couldn’t help but wonder how close image-generating AI was to taking away my other job – photography, the one I actually care about far more. So I set up a Discord account and signed on to Midjourney’s server for an experiment in AI photography, to see what the software was capable of doing, and if it was merely months instead of years from making me obsolete.

I had just a couple of dozen freebies on my Midjourney newbie account, and after wasting two or three trying to figure out the prompts, I tried something simple, and asked for it to create a “Black and white portrait of a middle-aged male actor in London in the Sixties.” I’m going through a bit of a Swinging London phase right now, which involves obsessing over the work of famous British photographers like David Bailey, Brian Duffy and Terence Donovan, as well as contemporaries of theirs like John Cowan, David Montgomery and Eric Swayne, whose posterity has dimmed in their colleagues’ long shadow.

The result was startling. The software had created a face that echoed but didn’t quite resemble that of a Laurence Harvey or Richard Todd. At a quick glance the modeling of the light looked not just accurate to simple physics but contemporary style; a bit more pre-Beatles than I’d had in mind, more like a studio publicity handout than an editorial assignment for a Sunday colour supplement, but then my prompts probably hadn’t been specific enough. I needed to force the software to drill down a little more, to search through the millions of images that it had scraped on the websites of stock agencies and museums and magazines and photo agencies.

I tried again, writing: “Black and white portrait of a young blonde British actress in the Sixties lit by a window.” The result was disappointing.

It was certainly far less photorealistic than my first request – more like a portrait painted by a skilled illustrator who had been academically trained in some decent but second-tier art school back when artists made decent livings on commissions from popular magazines, book publishers, ad agencies and movie studios. I had expected Julie Christie in Billy Liar or Susannah York in Kaleidoscope. The subject of this portrait looked pretty enough, but jarringly generic and nowhere near human.

Like so much of the AI art I’d seen, it had a faintly kitsch aspect; much of the work I’d seen created in Midjourney evoked the artwork on mass market sci-fi paperbacks published when I was a kid. The software had somehow grasped the era, but not the precise (and exhaustively archived) photographic look I was hoping it would discover in its vast memory.

I needed to try again, and I still had plenty of freebies.

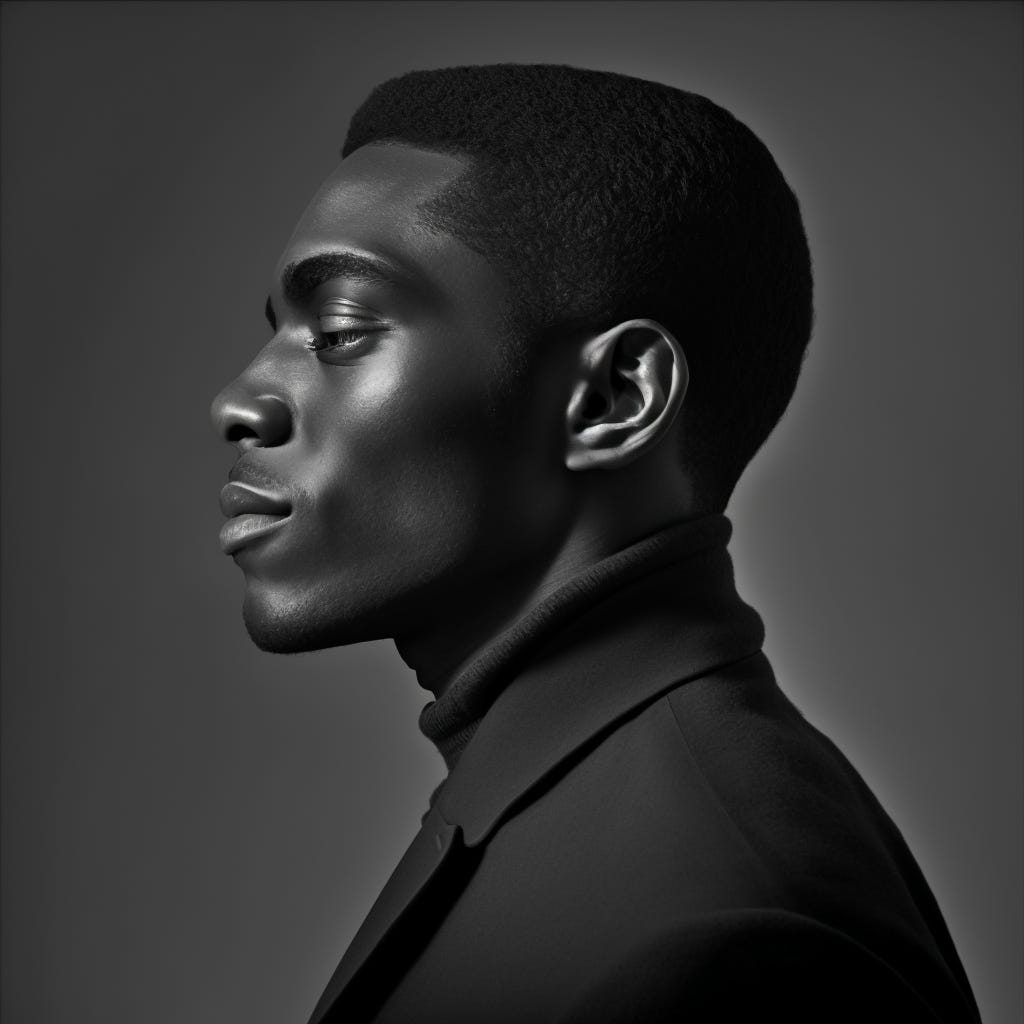

I typed the prompt “Black and white portrait of a black British musician in London in the mid Sixties in flat light in front of a grey backdrop in profile.” The result was much better. The software had picked up on the appropriate fashions and hairstyle, and had conjured up a face that I could imagine on a record sleeve. This could have been someone who played with The Equals or The Rudies.

Upon closer inspection, however, the image didn’t quite satisfy. The lighting was fine enough, but the skin tone it rendered looked plastic. I’d learn later that if I wanted to use up a few more of my freebies, I could have requested the software to upgrade the resolution to what might have been photorealistic quality but I was satisfied, so far, that Midjourney’s AI was able to reference the appropriate stylistic touchstones pointed to approximately in my inelegant prompts.

Staying in the vicinity of Carnaby Street in 1965, I wrote another prompt into Midjourney’s Discord newbie server: “Black and white portrait of a British model in the Sixties in the studio with big eyes in the style of David Bailey.” I knew that the AI understood instructions nudging it to ape the style of an artist, and that there were plenty of examples on the internet that the software would have scraped. I anticipated some strange, possibly unsettling combination of Jean Shrimpton, Twiggy, Grace Coddington and Penelope Tree, against a bright white seamless backdrop.

What I got…wasn’t that. The big eyes – a common trait that linked most of the top models working in London in the mid to late Sixties – were certainly there, and the hair and the clothes didn’t look jarring. But there were those white “freckles”, which appeared in all four of the options Midjourney delivered after my prompts, of which the AI was obviously quite fond.

And then there were the “googly eyes” or buttons in the model’s hair, which appeared in all four variations. (I chose the least obvious when requesting further upscaling and refinement.) It’s baffling unless you’re aware of the AI’s facility with the fantastical and sci-fi imagery of all sorts, which users have also noticed and encouraged over so many of the AI art social media accounts I’ve seen.

An anecdote in most of the press I’ve read about the rise of AI art involves Jason Allen, a games designer who won the blue ribbon in the Colorado State Fair’s annual art competition for “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial”, a very sci-fi inflected digital painting created with Midjourney. When news of his win broke, he was accused of cheating, and the artist and his work were attacked.

“This is so gross,” wrote one person on Twitter, as reported in a New York Times article. “We’re watching the death of artistry unfold right before our eyes,” wrote another.

Allen himself said he was astounded by the results the AI delivered. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” he told the Times. “I felt like it was demonically inspired – like some otherworldly force was involved.”

The judges at the art competition apparently knew nothing about Midjourney or AI art, but said that they would have given Allen the prize regardless.

“I’m not going to apologize for it,” he told the Times. “I won, and I didn’t break any rules.”

I’d read that AI software could be addictive, and I was feeling a growing flush of excitement when I composed my next prompt: “Black and white photo of young Terence Stamp wearing a striped shirt against a white seamless background in the style of David Bailey.” I wanted to see what it would do when directed to create a portrait of a real person, and I made sure this time to say “photo” instead of “portrait.”

I knew I had ordered a portrait of Terence Stamp (an actor I once missed a chance to photograph; I still wince about it) but I’m not sure that if you showed it to someone who didn’t know this that they’d see a resemblance. The plastic skin tone was there again, but I was impressed that the AI opted for that hint of stubble that Stamp sported in films like Poor Cow and Blue.

The shadow on the seamless behind him was baffling – the AI seemed to understand depth of field wonderfully, but for some reason it modeled the shadows as if the highlights on Stamp’s face were invisible. It also had very little sense of David Bailey’s distinctive studio style, despite abundant examples it could scrape off the internet.

I challenged it again with another prompt: “Horizontal black and white photo of a young British Mod outside on the street in overcast light in the style of Brian Duffy.” Midjourney, like most other AI software, defaults to a square image, probably to favour easy sharing on Instagram. There are prompts to make it produce different aspect ratios (I requested a horizontal shot to get it to favour images scraped from photos shot on a Pentax or Nikon) but I wasn’t aware of them.

The result returned was the most successful yet; it was palpably photographic more than merely photorealistic, and though the hair on my young Mod wasn’t appropriate to his particular subculture, the AI had done its damnedest to create a wardrobe for this young man (his expression suitably defiant and working class) that you might have seen on any night in the Goldhawk or the Marquee.

There were still little issues, however, like the extra small buttonhole on the right side of his too-wide lapels, and the buttoned flap over his breast pocket. And then there’s the half an extra collar beneath his tie on his shirt, which is the sort of thing that the AI is famous for throwing into images, like the extra fingers or even hands that appear in so many images, or books with extra covers or spines or floating sets of pages.

This is the visual equivalent of the AI tendency described by Rebooting AI author and NYU professor Gary Marcus when he was interviewed by the New York Times about text-generating AI – a “pastiche generation” that makes the software behave like “high school students who plagiarize and change a couple words here or there but they’re not really putting ideas together. It doesn’t really understand the underlying ideas.”

I changed my approach for my next prompt, writing: “Photo of a London photo studio in the 1960s lit by a skylight with a camera on a tripod, a stool, a light in an umbrella reflector and a white seamless backdrop in the background in black and white.” I wanted to see if the AI could imagine the space my London photographer would have called his home and office. Once again, the results were baffling.

I assumed there were plenty of photos of photographers’ studios online, and I had hoped it would retrieve whatever images it had scraped of Lord Snowdon’s skylight studio, or John Cowan’s studio at 39 Princes Place in Holland Park – the studio rented for David Hemming’s character by Michelangelo Antonioni when he filmed Blow Up.

What I got was a much meaner looking space, with a suitably white-painted brick wall you might have seen in a recently-renovated stables or garage (though a photographer might have been inclined to paint those bricks black). The seamless had become a shoddy batch of bent white cardboard panels propped against the wall. And you could plausibly guess that the pool of light in the foreground might have come from a very small skylight very high in the ceiling overhead.

But it was the camera gear that made me shake my head. The tripod disappeared entirely, and what I assume the AI called a camera was left sitting on the wooden stool. The light stand looked plausible, but the umbrella reflector was only notionally so, and the strobe head it was mounted on looked utterly weird, with or without the random scraps of wiring attached to it, to the stand, and littering the floor.

I had hoped for a Rolleiflex or a Hasselblad on a tripod; what the AI delivered resembled the institutional A/V equipment I remember from my school days in the ‘70s. Was this the “shockingly clueless…child prodigy,” taking in endless information at a glance without really understanding what it is and does, outfitting a photographer’s studio with whatever it could recall in a second about cameras or photography based on a few memories retained while endlessly distracted?

I’d probably have done the same thing myself as a child, and had a sudden pang of sympathy for the AI, being tasked with providing miracles despite its age and callow understanding of the world.

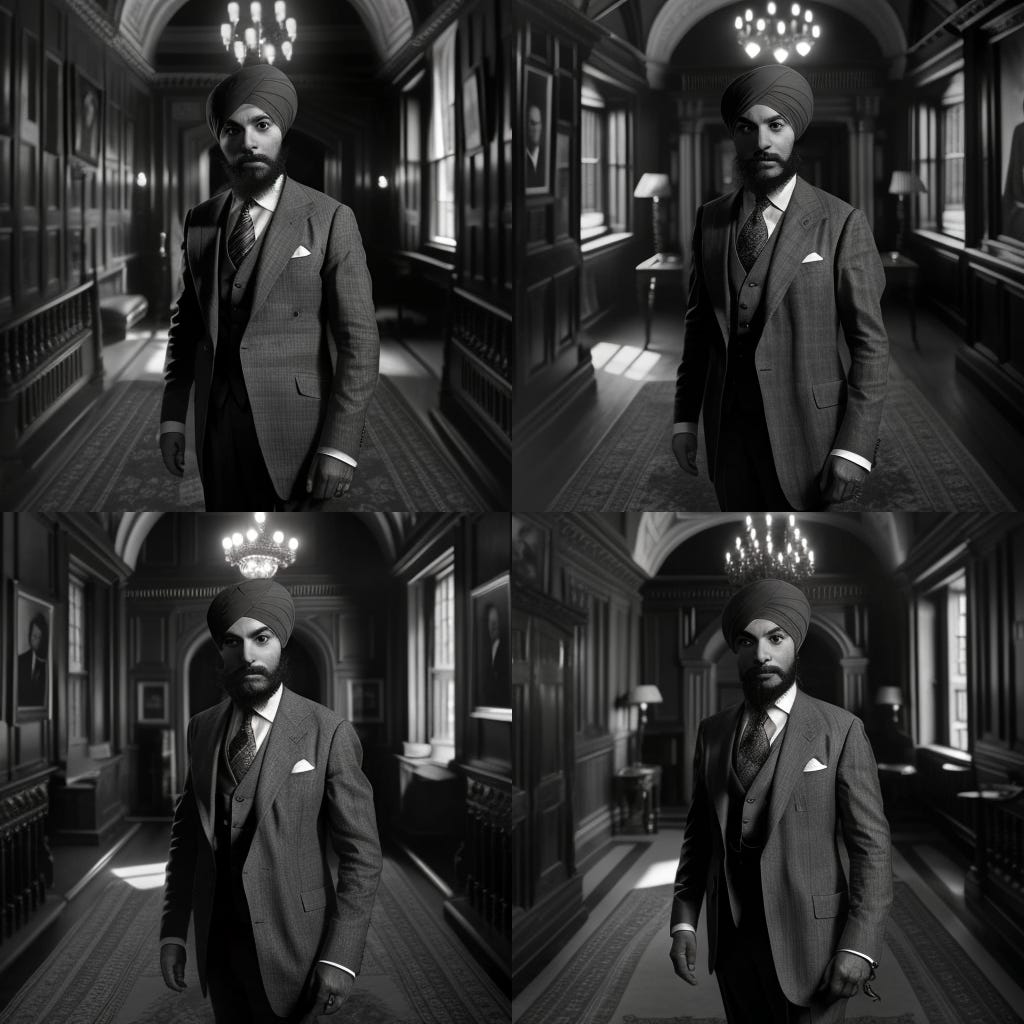

I made one more quick prompt before leaving Harold Wilson’s London, a “Photo of a British Sikh politician in a pinstripe suit in the hallway of the House of Commons in the style of Brian Duffy.” My alternate history had grown to include a Labour member in his first term, the son of a cinema owner who would hold on to his seat through the turbulent ‘70s before losing it in Thatcher’s Tory landslide, becoming chairman of ITV in the ‘80s and a peer in the ‘90s: Lord Singh of Ealing, predecessor to Baron Suri.

The AI did a pretty fine job with its four options, creating the man, dressing him appropriately and filling out a very realistic paneled hallway behind him. The lapels put him in the Commons at the end of the decade, and his expression in at least two of the shots hinted at a taught internal life, though there really wasn’t anything there to suggest Duffy as much as any other competent shooter with a freelance front-of-book editorial assignment for the Sunday Times Magazine.

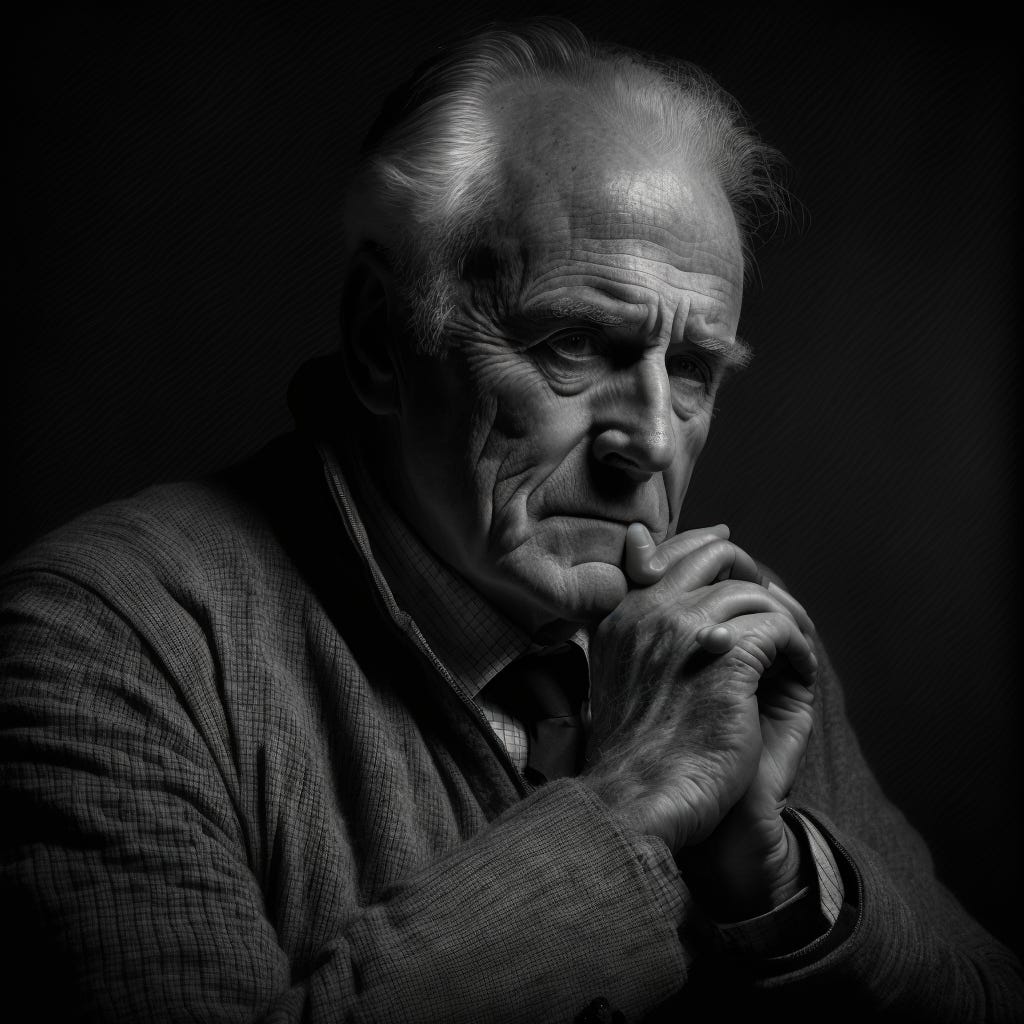

Finally, I was ready for the experiment I’d had in mind since signing on to Midjourney. I typed the prompt: “Black and white portrait of older British writer in a tweed jacket and tie in window light, hands by his face in the style of Rick McGinnis.” I didn’t anticipate that the AI had developed any sense of me or whatever might be my photographic style, and after seeing what it had delivered when I’d pointed in the direction of much more famous photographers, I didn’t imagine that it would now.

I’d chosen my prompts carefully; I spent much of my career in the ‘80s and ‘90s – to my memory at least – shooting writers and directors, older men more often than not, back when newspapers and magazines still gave space to articles on writers. I wondered if the AI would be able to scrape together enough information from whatever Venn diagram my prompts suggested to create something at least remotely familiar. I had certainly done my part seeding the internet with my work.

There are the usual strange AI decisions, like the way the subject’s skin and “tweed” jacket seem made of similar material, and their anatomically curious hands – a collection of digits, at least one of which has melted into the other hand. Apart from that, it looks like the sort of photo I might have taken back in the ‘90s, in five minutes or less after the interview was over, in some dim hotel room with available light on my tripod mounted Rolleiflex. My photo editor for much of the decade would have judged it a bit too dark for newsprint at the time, but I’d have happily rediscovered it twenty years later for my old blog and proudly posted a few scans.

Authorship is probably the biggest potential problem with AI art, and most creators are already taking to the barricades in anticipation of every new instance of AI mimicry turning into actual theft. Stock agencies will be the first hit by AI as it provides generic images to order on its way to creating better and better depictions of real people and things. Getty Images has banned imagery created with AI, citing “open questions with respect to the copyright of outputs from these models.”

But competitors like Adobe Stock and Shutterstock have been willing to make deals about creating and submitting AI imagery, wisely assuming that it’s better to begin dealing with the growing hive mind while it’s still in its infancy and before the public has begun blithely accepting AI-created work amidst the overwhelming cascade of images they take in every day.

Because the public at large doesn’t feel the same stakes at play with AI that creators do; a recent article in the Guardian noted that “AI image generation has the potential to do away with smaller jobs that up-and-coming artists often rely on to build up portfolios. (Illustrator Anoosha) Syed says that for things such as fan-art, self-published books, logos and family portraits, people may turn to AI. ‘These clients will usually care more about saving money than the quality of the finished product,’ she says. ‘They will prefer to use AI if it means keeping costs low. So a lot of these small jobs will vanish.’”

With my freebies almost gone, I finally decide to test Midjourney with a task that I’m sure most people think about when they discover the AI’s potential. I write the prompt: “Photo of Rick McGinnis in black jeans and a black shirt in a pool hall shot in the style of Chris Buck.”

Thanks mostly to my own efforts, there are at least a few portraits of me at different stages of my life on the web, and at least a few of these have been made by my friend Chris, a well-known editorial and advertising portrait photographer whose reputation is positioned somewhere between my own and Bailey and Duffy’s. Moreover, Chris’ style is distinctive enough that even the laziest, most overworked AI might be able to take a wild stab it mimicking it.

But the results aren’t even close. I won’t bother with my “likeness” – the man in this picture resembles no one I have ever been or will look like. (I even tried to make it easier for the AI by requesting a wardrobe that matches the last time I sat for Chris.) The light is all wrong, as is the composition and the use of the setting; this looks less like a Chris Buck than an image created for a mid-sized print ad campaign twenty or thirty years ago. A solid D-.

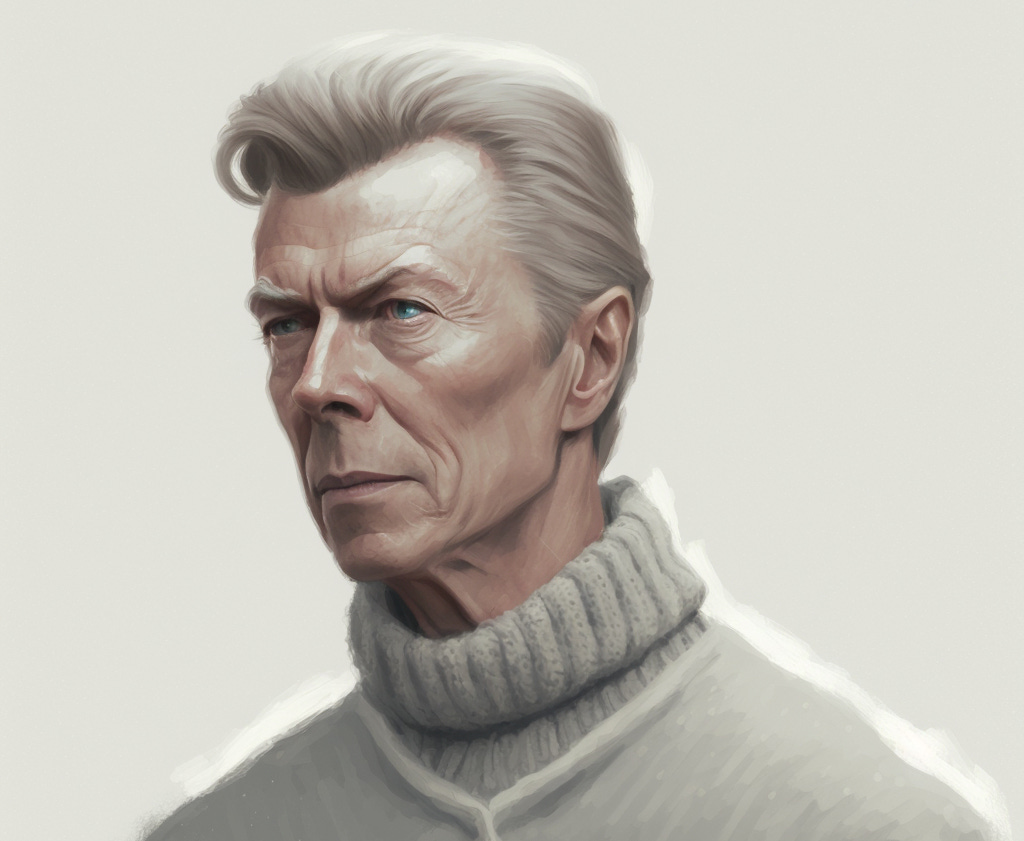

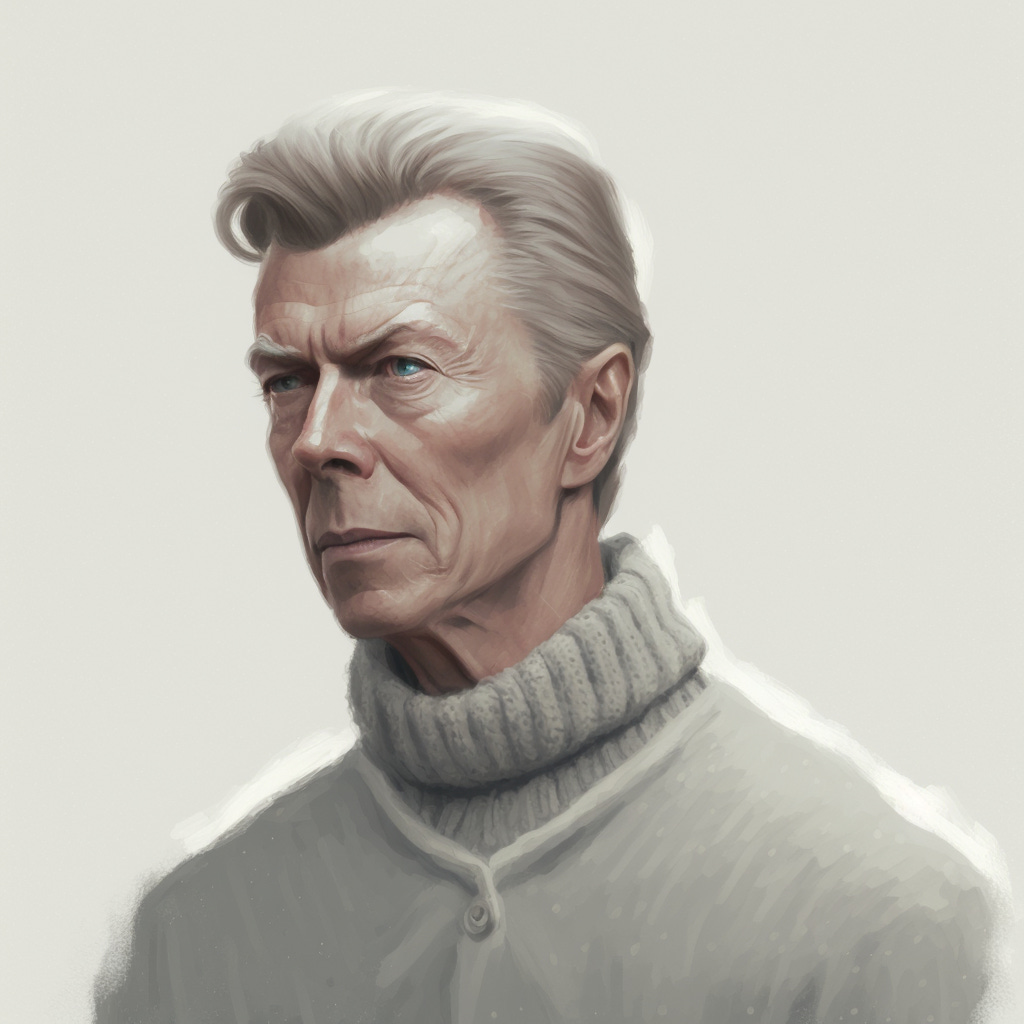

With just one roll of the dice left on Midjourney, I indulge in another career fantasy and write the prompt: “Portrait of an older David Bowie wearing a grey sweater in flat light against a white backdrop in the style of Rick McGinnis.” David Bowie had always been on my wish list of portrait subjects, a figure of huge cultural importance to me who I had only managed to photograph once, in concert (then promptly forgot I’d done so for nearly three decades).

What if he hadn’t died seven years ago, and what if I’d been able to revive my career as an editorial portraitist enough to get the assignment to take his portrait, five or maybe ten years from now? Maybe while he was doing publicity for an updated version of David Bowie Is…, the hit touring exhibit that my whole family went to when it made a stop in Toronto ten years ago.

There are obviously enough photos of Bowie out there for an AI to render a decent portrait. (I can’t help but imagine that Bowie would have found this whole AI moment fascinating and inspiring; it’s the sort of cultural mutation that would have led to a whole new creative period.) The AI definitely delivered a satisfactory likeness, suitably aged, and in the kind of stark lighting scheme that I’ve favoured in my own recent work, though I doubt that any of those photos had a part in generating what is ultimately a very simple portrait.

But the omission of the word “photo” resulted in something more like a painting than any previous product of my long afternoon on Midjourney. It makes me certain that it will be painters and illustrators, not photographers, who will the first to really suffer as AI image generation becomes more acceptable. Certainly my “Bowie portrait” puts me in mind of a painter like John Currin far more than a photographer like myself.

But there aren’t that many photographers, and far fewer ones who actually make their living from their cameras, and our feelings really don’t count for much in the end.

Articles on AI threats to photography love to quote painter Paul Delaroche seeing his first Daguerreotype in 1840 (“From today, painting is dead.”) or Baudelaire calling photography “art’s most mortal enemy.” Jason Allen, the blue ribbon-winning digital artist suddenly so central to the story of AI over the last year went so far as to say “Art is dead. It’s over. A.I. won. Humans lost.”

Which might be true, but twenty years ago I remember a lot of photographers saying unequivocally that digital technology was going to kill their art. Not only did that not happen, but a revival of analogue film photography has happened since nearly every professional I know ditched their SLRs.

Which isn’t the same as saying that we don’t have anything to worry about. Copyright and intellectual property are definitely an issue, and one that will get a lot worse before anything like a solution emerges.

“Art is dead. It’s over. A.I. won. Humans lost.”

What I’m really worried about, though, is the moment some young art director with a lot of time and talent but very little budget responds to demands from their bosses that they slash the editorial budget even further by signing on to DALL-E 2 or Midjourney and crafting a set of prompts that results in some undeniably interesting and publishable images. (I have lost track of the number of emails I’ve received from photo editors that include the words “we really don’t have much of a budget for photography.”)

They will solve a problem, and they will reap the rewards.

I’m sure that’s what my photographer colleagues are worried about when they waste a couple of days writing prompts and marveling at the results. (While ultimately becoming tired and bored with the whole exercise, which – if my own feelings are worth considering – is ultimately less rewarding than going out and shooting something.) But there aren’t that many photographers, and far fewer ones who actually make a living from their cameras, and our feelings really don’t count for much in the end.

The people who really matter are that creative, harried young art director who’ll end up winning a lot of awards, and the thousands - probably millions - of people who will be able to make an end run around their lack of talent or commitment to what’s as much a craft as an art form, and simply want to find a way to express the images locked in their heads.

Because those are the people who have made the technological revolutions of the last two or three decades possible – the ones that have removed gatekeepers, abolished time and distance, helped create unforeseen new communication platforms, and made job titles out of “content creator” and “influencer.” I have little to no role to play in their journey to self-realization, though my participation in the imminent AI revolution is a matter of choice, at least at this moment, while the AI teaches itself every second, on a thrilling learning curve that I can’t help but envy.

I only wish it had the capacity to enjoy it while it can, and perhaps one day it will.

Rick McGinnis is a Toronto-based photographer and writer.